Big Top

I was born in the Bronx. I lived there as a young kid. My brother lived there into his early teens. My parents for most of their lives. I visited often. But I grew up in the New York suburbs. Fully (and, even now, a little ruefully) bridge and tunnel.

Like many suburban Jewish families at the time, we understood that a bar mitzvah mattered not only because it marked a big rite of passage, but because it offered an opportunity to stage a big, spectacular party.

My brother was the eldest and only son, and the day was treated accordingly. My parents rented a massive tent, a kosher barbecue, and a bar. There were Hebrew National hot dogs, Empire chickens, Manischewitz, pareve cake, and Dr. Brown’s sodas. Black cherry and cream (no Cel-Ray soda, to my father’s disappointment).

But this story is about something smaller, and stranger, than that.

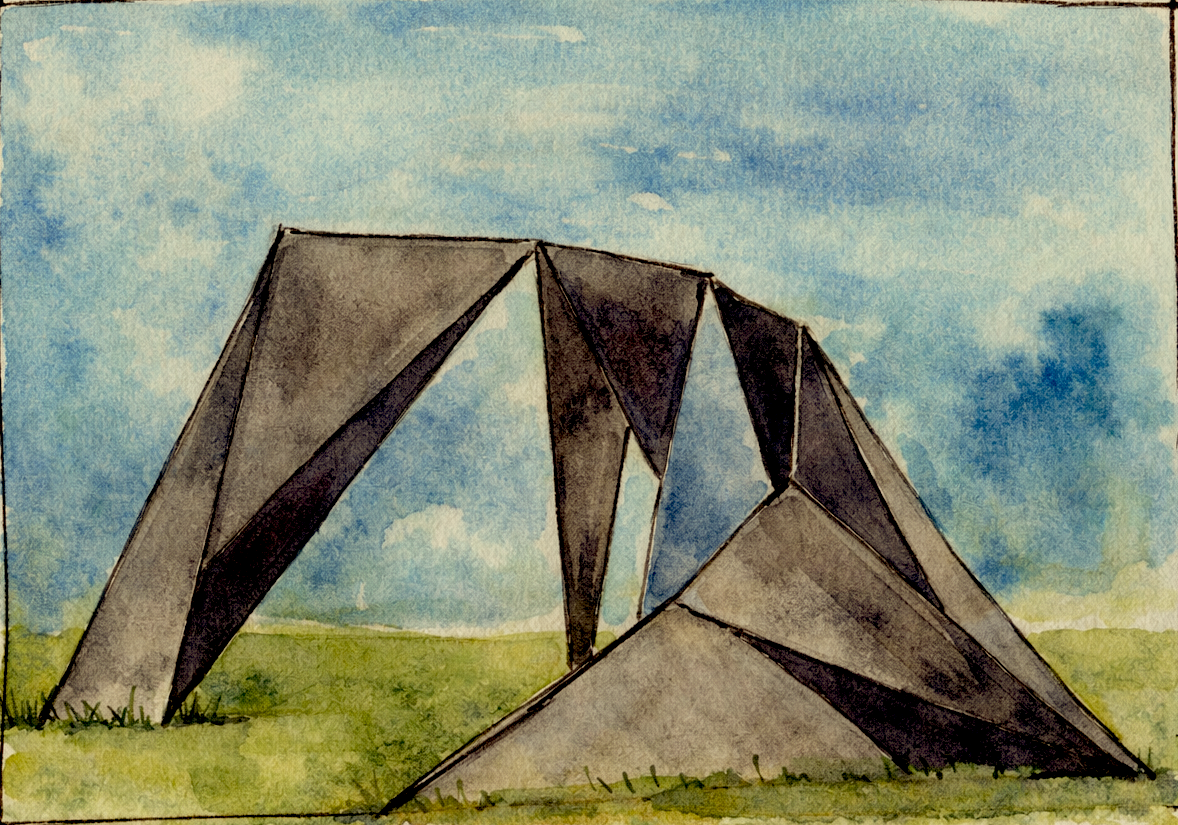

The day before the bar mitzvah, the tent top was spread across the backyard, laid flat on the grass. The crew would raise it the next morning while we were at shul, watching my thirteen-year-old brother “become a man.”

That afternoon, I was outside. Six years old. I walked the perimeter of the canopy. Took it in. Touched it. Felt its weight. And then I dove in.

This was not typical behavior for me. I was a cautious child. More Elliot than Goonie. A Linus-with-a-blanket kid. But something pulled me under.

I rolled around beneath the tent for a long time. The light thinned and softened, filtered through into a pale, underwater-like haze. The outside dimmed. I could feel the grass beneath me, cool and real, but above me was this vast, quiet expanse. Heavy sheltering. It felt like another world. Wonder, awe, and stillness

After a while, I was ready to get back to the world. But I’d gotten myself trapped. I couldn’t roll my way out of the tent. It didn’t occur to me to stand up or to even crawl. I. I just kept rolling, stuck beneath the canvas. Panic came quickly. I cried. I screamed. This felt unbearable. Where was my mother? Would I ever get out? Would I suffocate? Would I die?

After some time, I heard my mother calling. “Cara-lynn? Cara-lynn Michelle? Where are you?”

“I’m here!” I yelled tearfully. “I can’t get out.”

Then I felt my mother’s hands. From outside the tent, pressing gently just above where I was lost. And I calmed. I was still under the canvas, but I was with her hands. She nudged me out from underneath. I don’t remember much after that. I imagine that I cried, and that, clutching my mother, I felt safe and better, warm and found.

What stays with me isn’t the panic. It’s her hands. Patient as they were and are.

I still think about them. On that day.

More soon.

So. Much. Love.